Ottoman period

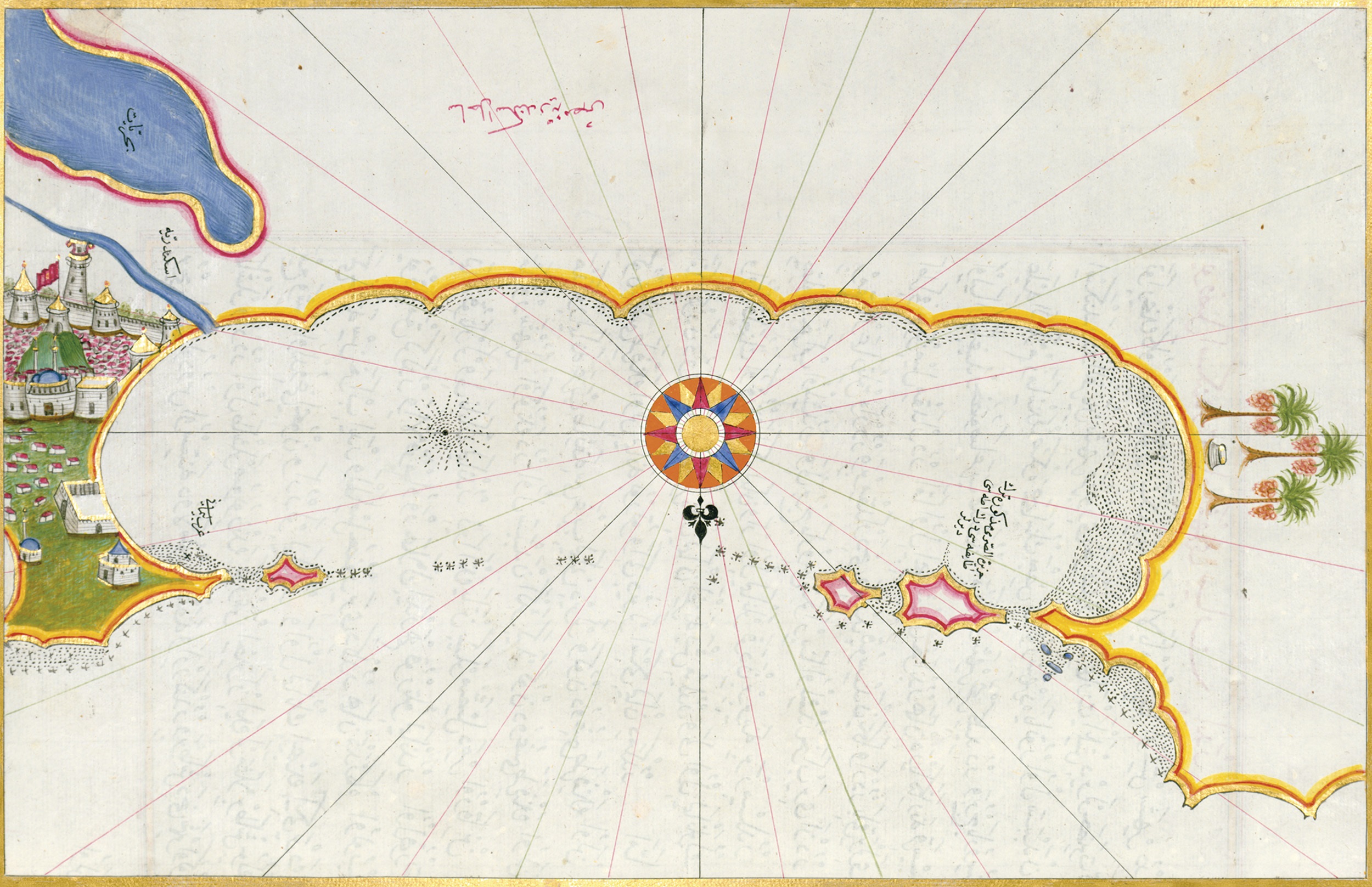

Charts of the town and coastline of, Alexandria Piri Reis, Kitab-i bahriyye, 1525 (17th century copy) © The Walters Art Museum

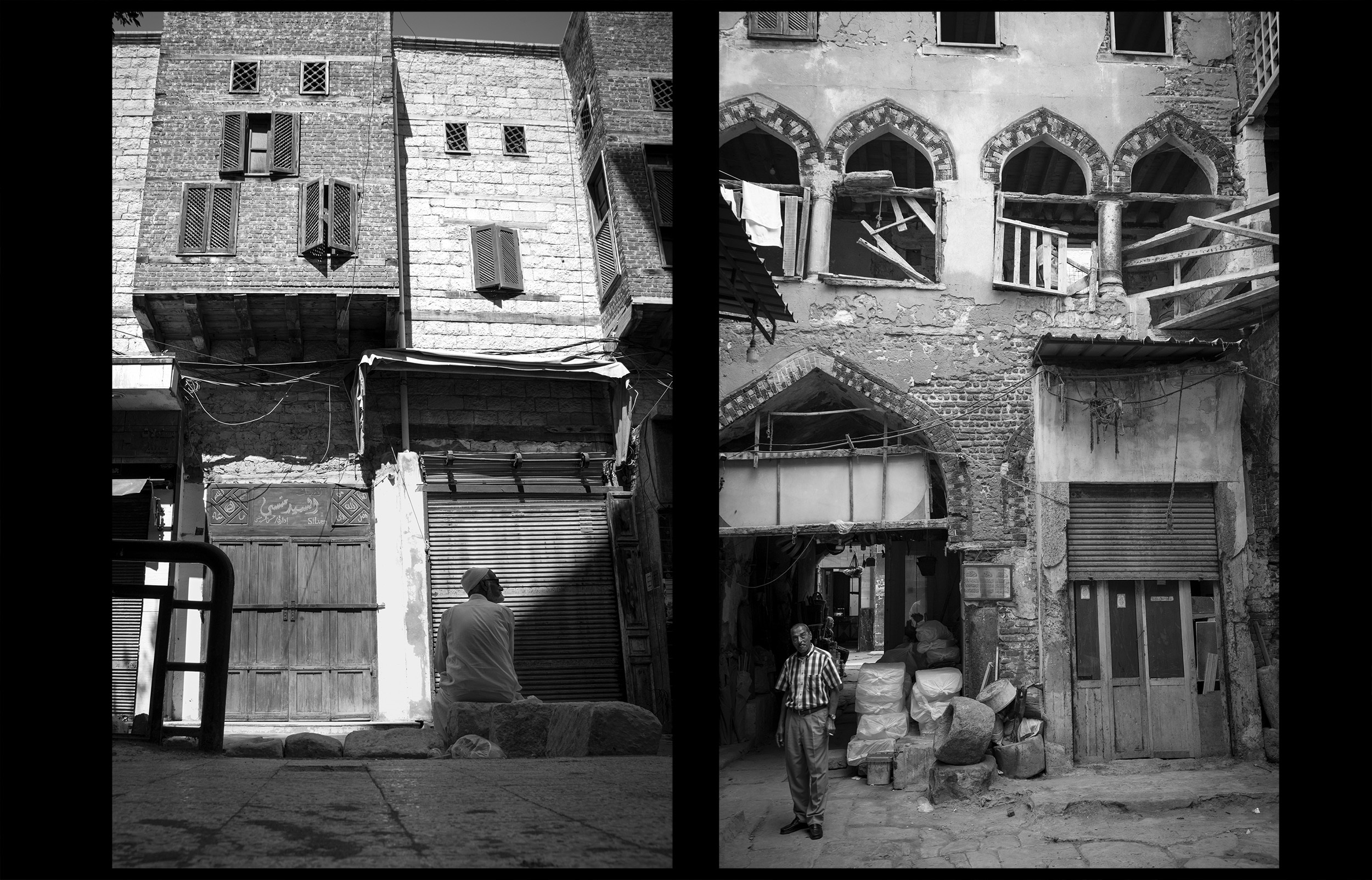

In 1517, Ottoman troops seized Cairo and Egypt became a province of the Ottoman Empire. Alexandria, which was very open to the sea and to maritime trade, benefitted from the new geopolitical situation. No longer a frontier town, the danger of attack was reduced and Alexandrians began to abandon the fortified medieval town to settle on the peninsula outside the city walls, closer to the harbours. In the 17th century, the new city, with its mosques, shops, wekalas and fonduks (inns), was being built, as described by Evliya Çelebi and other travellers. The Ottomans maintained the division of the two harbours: the harbour of “Infidels” to the east and the harbour for Muslims and the imperial fleet to the west. Shortly after the conquest, the Ottoman sultan had a new fort and an arsenal built there. However, during the 18th century, Alexandria went into decline and its harbours were abandoned. With the canal no longer navigable, ships had to sail along the coast to gain access to the Nile, and Rosetta became a more important port for transporting goods.

Photographs of the wekala Shorbagi, an inn/trading post in the Ottoman quarter, 2022. É. Forestier © CEAlex Archives

Johann Helffrich in Alexandria,1566

« Fondiques are trading posts with accommodation, as the inhabitants do not allow foreign Christians to scatter around the city and have their own dwellings. This is why each nation must have its own house called a fondique, to which the King of France sends an ambassador or, as he is called, a consul… These buildings are all square, but they vary in size… They have two floors. On the upper floor, there are lots of small rooms where the merchants are lodged. On the floor below, there are other rooms where they can store their goods. These fondiques have only one door that opens onto the street, and a Moor is in charge of closing it in the evening and opening it in the morning. In the evening, before closing the door, he uses a hammer to strike several blows on a specific piece of iron fixed to the door to warn anyone outside to come in. As a result, no one can get in at night.»

Piri Reis describes the harbours in 1517

Piri Reis, a Turkish sailor and cartographer, was born around 1465 in Gallipoli. He took part in several maritime expeditions, which enabled him to acquire an excellent knowledge of the Mediterranean and the art of navigation. In 1513, he completed his first map of the world, with the Atlantic in the centre and showing the adjacent parts of Europe and Africa and the New World. Piri Reis claims that he drew on both Eastern and Western sources to produce it.

Around 1518, during a trip to Egypt, he produced several maps of the Alexandrian coastline and important ports. The Kitâb-i Bahriyye (Book of Navigation) was completed in 1521 and republished in 1526. This novel work contains both maps of Mediterranean ports and nautical instructions. In 1547, Piri Reis was appointed admiral of the Ottoman fleet in Egypt. After a defeat in the Persian Gulf, he was sentenced to death in Cairo in 1554.

Evliya Çelebi describes the Western Harbour in 1672

Evliya Çelebi was born in Istanbul in 1611. His real name is unknown; Evliya is a pseudonym and “Çelebi” was a title designating a learned Turkish gentleman. Born into a wealthy family, he received a good education and was recruited into the service of the court of Sultan Murad IV. From 1640 onwards, he embarked on a series of long journeys around the Ottoman Empire, compiling his travel accounts in a ten-volume work, the Seyahatname, the 10th of which deals with Egypt. Evliya describes everything that strikes him as remarkable: towns, monuments, fortresses, people and their customs, clothes and festivals. Written in the popular Turkish language of the time, his literary style was livelier than the Persian-influenced style used by his contemporaries. In 1672, he arrived in Egypt and visited Alexandria, where he stayed for a month. He remained in Egypt until his death in 1683, staying in the citadel of Cairo.

1. “Map of the town and harbours of Alexandria” At the end of the 18th century the town was entirely concentrated on the isthmus while the medieval fortifications were completely abandoned. Watercolour, Louis-Jacques Bourgeois, circa 1799, 1/4,000 © SHD

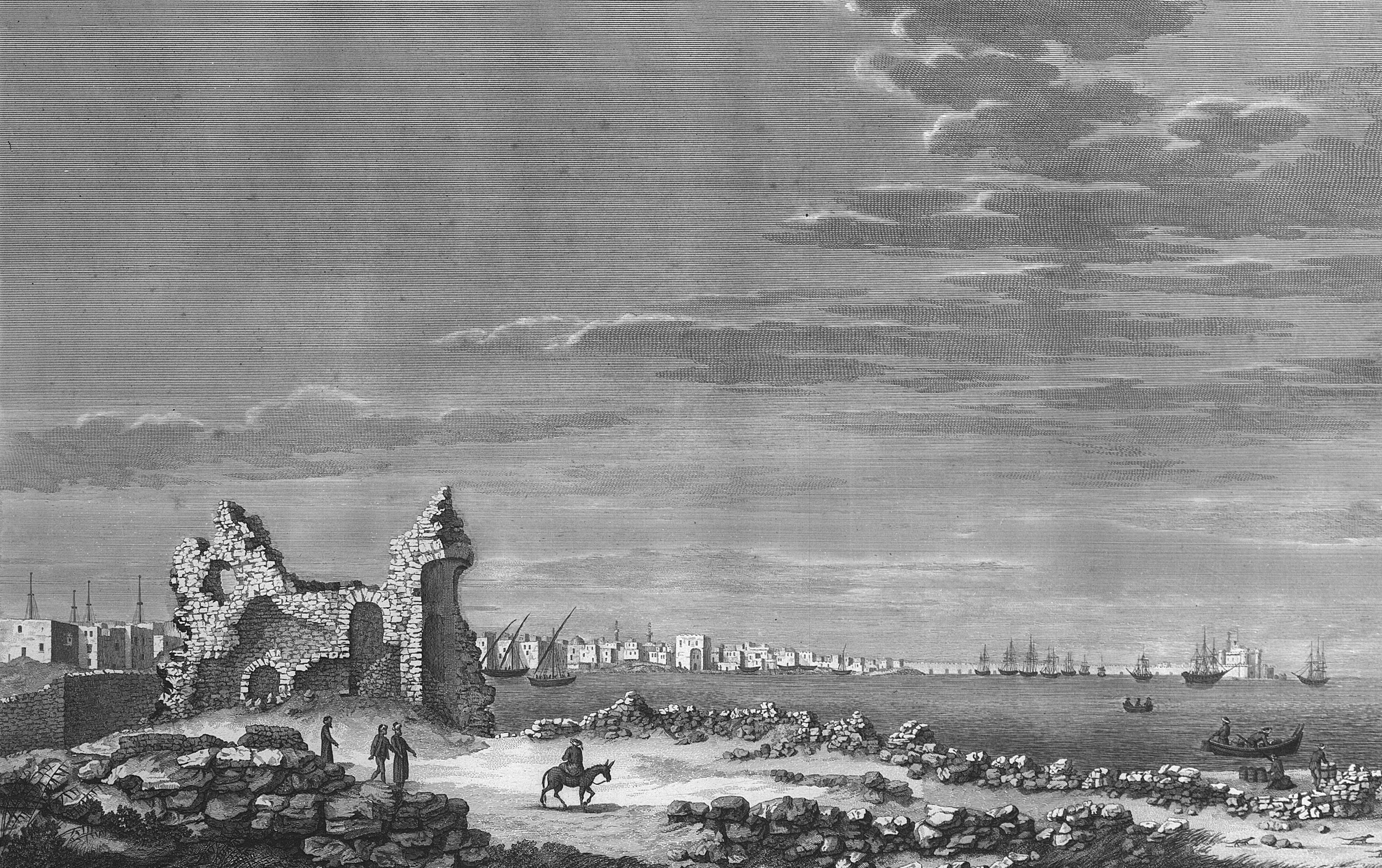

2. “View of old Alexandria”. Drawing by the Danish explorer Frederick Norden (1708-1742), Travels in Egypt and Nubia, vol. I, pl. VI, London, 1757 © IFAO library

3. “View of the town and the New Harbour of Alexandria from the to the Meidan” Drawing by the Danish explorer Frederick Norden (1708-1742), Travels in Egypt and Nubia, vol. I, pl. V, London, 1757 © IFAO library

4. “View of the town and the New Harbour of Alexandria from the Great Pharillon to the powder tower” Drawing by the Danish explorer Frederick Norden (1708-1742), Travels in Egypt and Nubia, vol. I, pl. III, London, 1757 © IFAO library

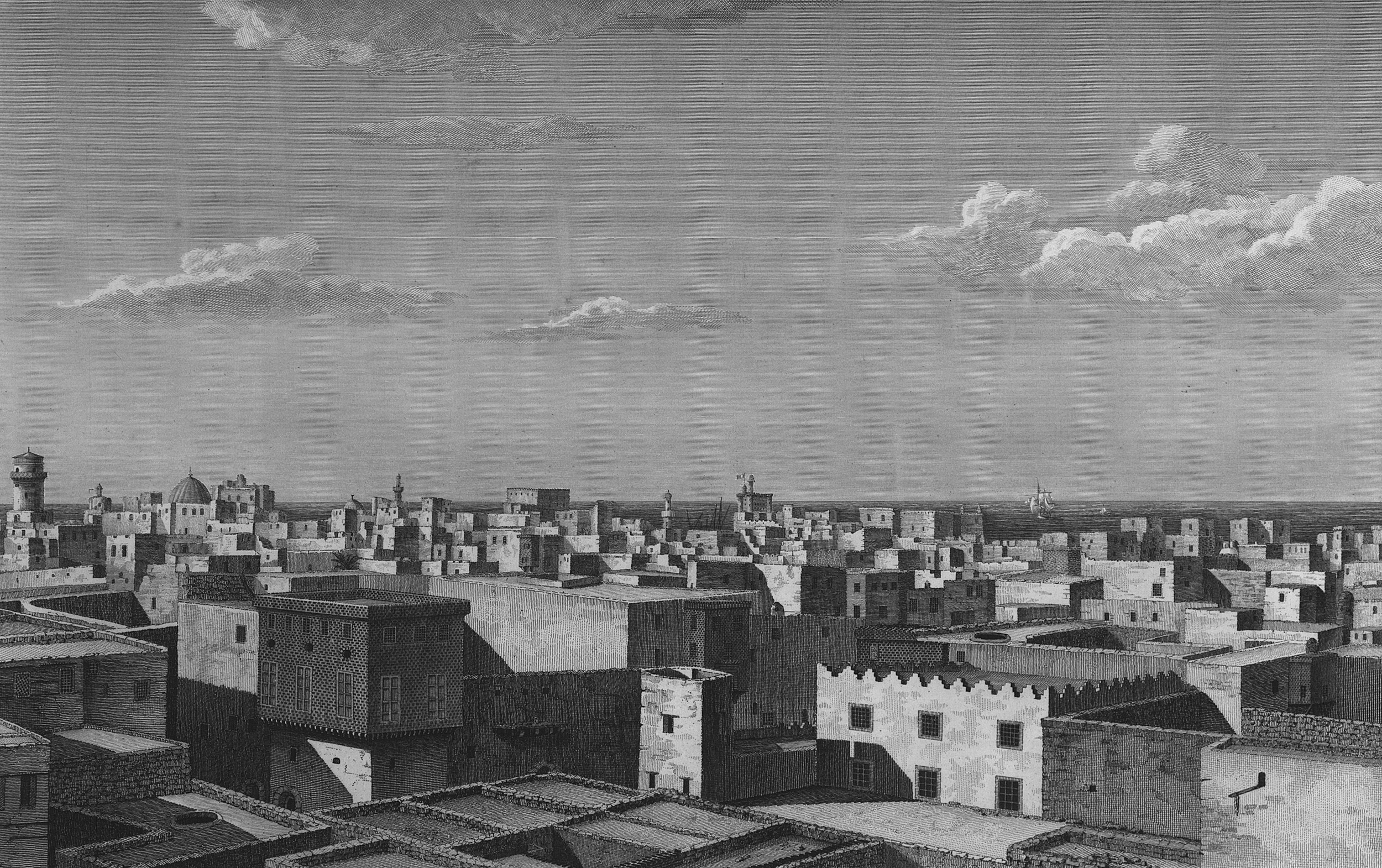

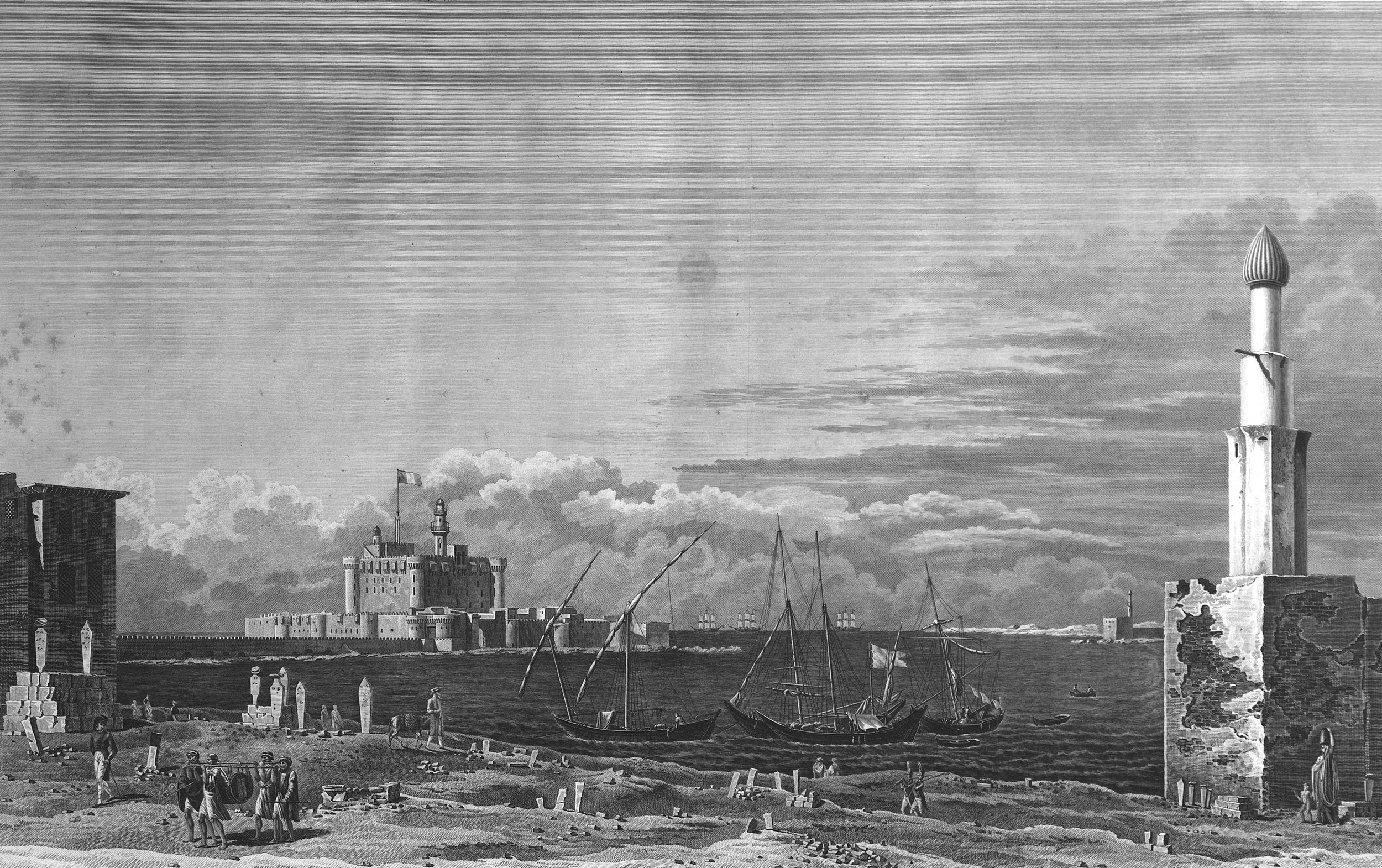

5. “View of the New Harbour from the south-west shore” in 1798. Intaglio engraving, Nicolas Conté, illustrator, Pierre-Gabriel Berthault, engraver, Description de l’Égypte, État moderne, Planches, Vol. 2, pl. 86. Collection J.-Y. Empereur © CEAlex Archives

6. “View of the rooftops of part of the town” in 1798. Intaglio engraving, Nicolas-Jacques Conté, illustrator, Pierre-Gabriel Berthault, engraver, Description de l’Égypte, État moderne, Planches, Vol. 2, pl. 95.2. Collection J.-Y. Empereur © CEAlex Archives

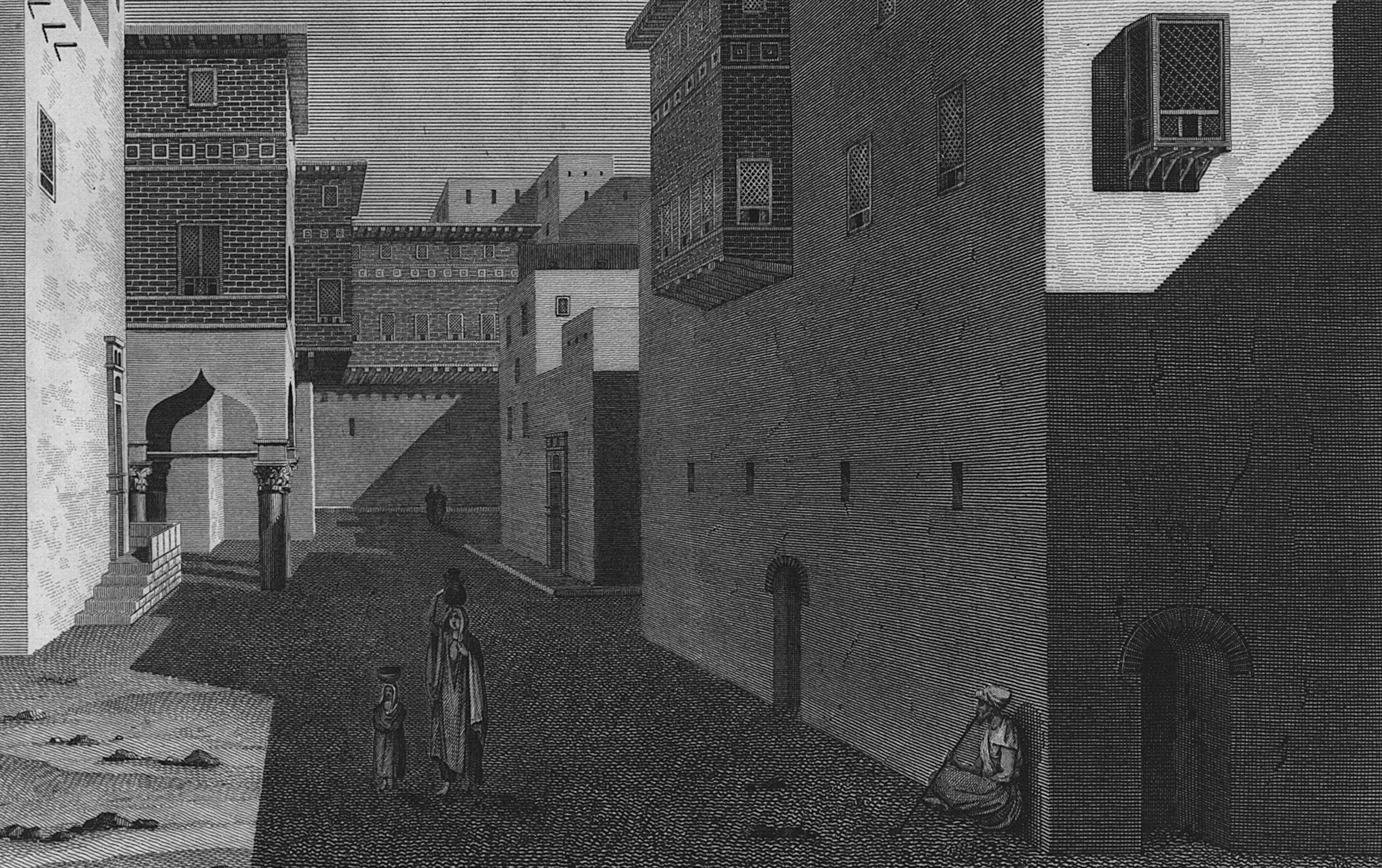

7. “View of a street leading to the Old Harbour” in 1798. Intaglio engraving, Jean-Constantin Protain, illustrator, Jean-Baptiste Reville, engraver, Description de l’Égypte, État moderne, Planches, Vol. 2, pl. 96.1. Collection J.-Y. Empereur © CEAlex Archives

8. “View of the New Harbour from the cemetery that separates it from the Old Harbour” in 1798. Intaglio engraving, Nicolas-Jacques Conté, illustrator, Louis Garreau, engraver, Description de l’Égypte, État moderne, Planches, Vol. 2, pl. 85. Collection J.-Y. Empereur © CEAlex Archives