Middle Ages

Alexandria, Piero del Massaio, Ugo Comminelli (copyist), 1474-1480. Bird’s eye view of the inhabited isthmus separating the two harbours, the medieval town, the defensive wall and moats, and the square structure of the Sea Gate. The high tower “Porta principalis” allowed access into the town. © BnF

Restricted enclosure

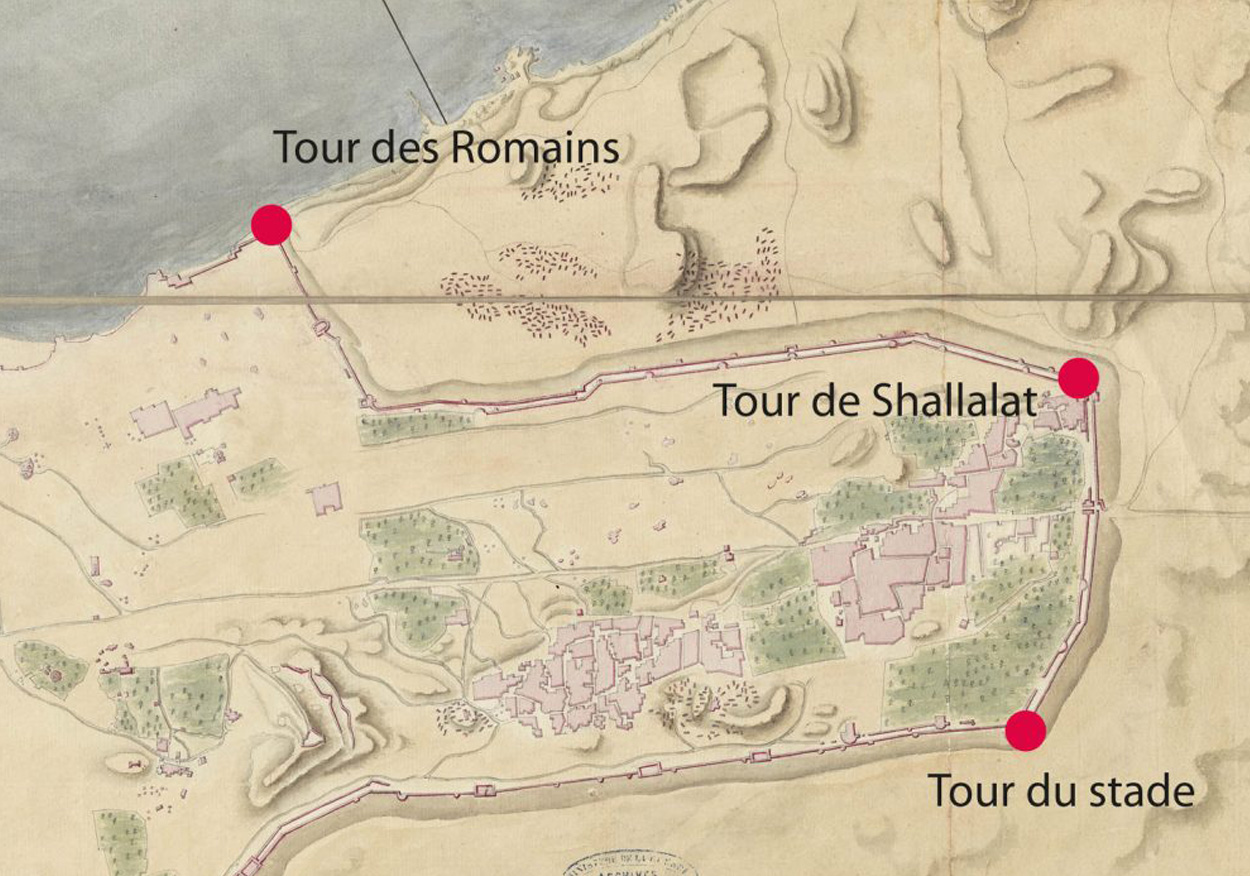

Over the centuries, marine sediments accumulated against the Heptastadion, forming an isthmus between the island of Pharos and the mainland and cutting off the passage between the two ports. After the Arab conquest in 642 AD and the founding of Fustat in the interior of the country, Alexandria lost its status as Egypt’s capital. Subsequently, the inhabited areas were increasingly concentrated on the peninsula and the two ports. Alexandria remained an important port city for maritime trade, but as a border town, it was exposed to attacks from the sea, and the various rulers sought to protect its inhabitants with powerful fortifications. Under Ibn Tulun in the 9th century, the vast ancient wall was abandoned and a new enclosure built on a smaller perimeter. The Serapeum hill, with Pompey’s Pillar, found itself outside the walls.

From then on, the inhabitants lived within the city walls and Alexandrians were strictly forbidden to settle on the peninsula. Only a few watchtowers stood on the isthmus between the two ports, including the Pharos of Alexandria, which was used as a military building.

The Sea Gate

In the Middle Ages, the defensive walls had at least five gates, two of which opened onto the isthmus to the north and the other three towards the Delta, the desert and the canal to the south. The main entrance for travellers arriving by sea was the Sea Gate, which also served as a customs post. This gate was a big square complex, fortified by three large towers, one of which (C) was used to control passage. Inside the Sea Gate, travellers would have their baggage inspected and pay taxes on any goods. Under the Fatimids (10th-12th centuries) and the Ayyubids (13th century), major fortification work was carried out, especially at the gates of Alexandria.

A Fatimid inscription on the Sea Gate read as follows: “In the name of God, the most beneficent, the most merciful… May God bless Our Lord Mohamed and all his family… The completion of this great fortress was ordered in the month of the First Rabi’ of the year five hundred and twenty-three [1128-1129]”

The Sea Gate in ruins, 1798, detail from Alexandrie. Vue de l’esplanade ou grande place du port Neuf et de l’enceinte des arabes, seconde part, Description de l’Égypte, État Moderne II, pl. 98, coloured. Collection J.-Y. Empereur © CEAlex Archives

The layout of the Sea Gate and line of the medieval wall against the present-day urban fabric of Alexandria. K. Machinek forthcoming © CEAlex Archives

Felix Fabri describes going through the Sea Gate in 1483

From Pharos to fort

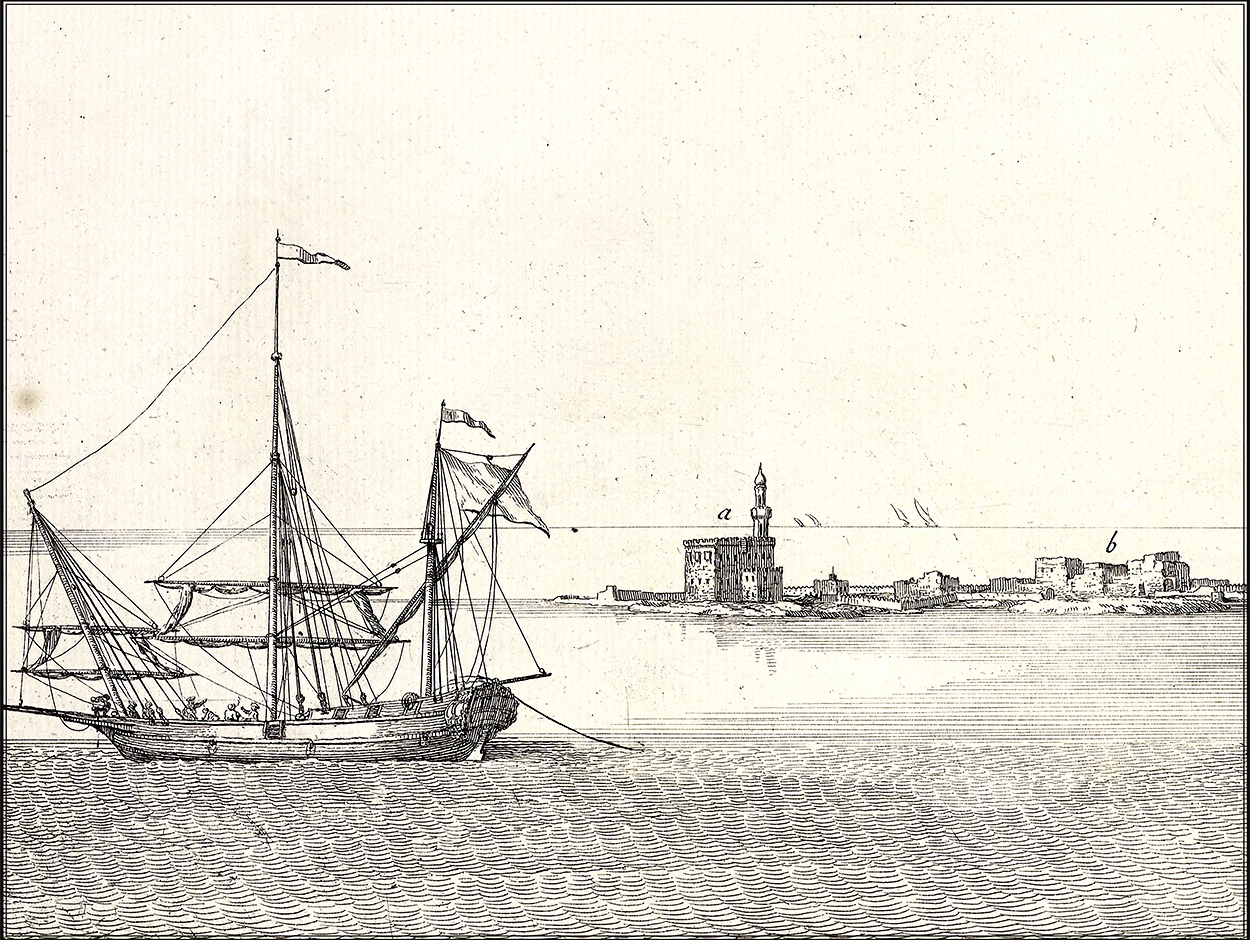

In 1303, the Pharos collapsed in an earthquake that destroyed a third of the town. From then on, the city’s defences were seriously weakened, and despite the construction of the Pharillon around 1330 on the cape opposite the ruins of the Pharos, the entrance to the Eastern Harbour was poorly fortified. In the autumn of 1365, the ships of Pierre de Lusignan, King of Cyprus, appeared off Alexandria. Under the pretext of a crusade, the city was ravaged and many of its fortifications destroyed. After this fateful raid, the authorities designated the Eastern Harbour as the only one open to Christian ships, to ensure better control of foreigners. The Western Harbour was only open to Muslims.

After the Ottoman conquest of Constantinople in 1453, the Mamluks feared that Egypt would be next. Thus, Sultan Qaitbay had a fort built on the ruins of the lighthouse, which Sultan El-Ghuri enlarged a few years later. He installed modern artillery and, by means of a decree engraved on a marble plaque, prohibited the theft of weapons on pain of death.

Zaccaria Pagani describes the harbour defences in 1512

Photograph of Qaitbay Fort from the sea, 2019. P. Soubias © CEAlex Archives